While we’re on a roll with music and metadata, let’s throw coronavirus and statistics into the mix because, like many people, I spent last year working mostly from home.

It’s an arrangement I’ve grown very fond of which, due to the work I do, the location of the colleagues I do it with, and the flexibility it offers, has actually increased my productivity. The ability to choose my “background music” may have also been a contributing factor.

Last year I also revised my audio hardware and ended up purchasing and processing more audio than I had in recent years — in both analogue/physical and digital formats, and I’ve been messing about with MusicBrainz and ListenBrainz. In hindsight, I went on a much further musical trip than I had remembered — but that’s not what this is post is about.

This post is about distorted data and false analyses.

In December, Spotify (“the world’s most popular audio streaming subscription service with 406m users, including 180m subscribers, across 184 markets”) released their annual report about insights gleaned from what their users listened to. That’s cute.

Obviously the report cannot include what the competition (Amazon, Apple, Deezer, Tidal, YouTube and the like — let alone Chinese behemoth Tencent’s 660 million users) have been streaming. The numbers are skewed — although it’s Spotify’s near-global reach that does shed some light-hearted insight for and about westernised audiences. That’s nice — but still not what this post is about. I don’t do Spotify.

What I did do was scrobble the metadata embedded within a stash of local MP3 files — usually playing “100 random songs” as background music while going on with my salaried work or other activities. Sometimes I felt like hearing electronica or dance music, occasionally I cranked up a random selection of hard rock and metal, and never would I voluntarily play Bob the Builder, Het Smurfenlied or hip-hop — but that’s the curse of randomness. In fact, J. River Media Jukebox has a knack of coming up with truly serendipitous song pairings. Also: Ambient music should be avoided during night shifts. That’s counter-productive.

Meanwhile, digital discoveries and duties at Discogs meant that I also listened to myriad releases by independent artists and/or netlabels. These are typically played only while and for as long as I’m busy hammering the data into Discogs.

Chances are I will never hear many of them again because not everything’s worth keeping (along the lines of “submit and delete”). These also got scrobbled.

What didn’t get scrobbled was physical media in the form of tapes, CDs, shellac and mostly vinyl records that got thrown out afterwards. In fact, Last.fm offers a slew of plugins and APIs that allow users to scrobble from a variety of online services over and above manual entry — fostering compulsive behaviour and/or distortion of actual plays.

Likewise, there are a surprising number of services and tools that can analyse your listening habits (read: that which you chose to scrobble). I had no idea this was a thing but it’s certainly a rich data set for aspiring data analysts to play with.

Fun fact: My first scrobble was Queen’s Flick of the Wrist on Nov 11, 2007.

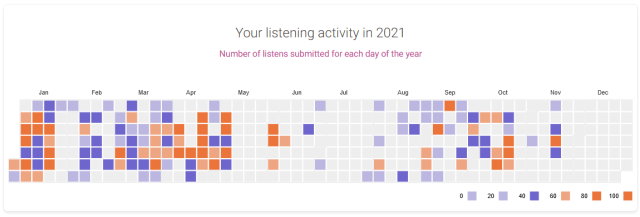

And this brings us to 2021’s statistics and recommendations: Last.fm has a personal profile on me. So does ListenBrainz, because I’ve imported last year’s 7052 scrobbles to see what different insights they would offer. Oddly, ListenBrainz only shows 6720 listens for the last year. We’re off to a credible start!

My top artist for 2021 is Kylie Minogue.

This surprises me — although it shouldn’t: I have a vast number of old remixes and mashups of her work so that a selection of “100 random songs” statistically must include more Kylie Minogue tracks than anyone else’s. So here we have meaningless information that does nothing but remind me that I’ve been lazy and must get to ripping the rest of my Queen CDs. I own the lot — I just haven’t ripped them yet. Urgh! More stuff to do!

As for Spotify’s top artist for 2021: Who the fuck is Bad Bunny?

I’m clearly out of tune with current music because, not unlike the generation before me said, “It sounds like shit. Music was so much better when I was a kid.”

On a more positive note, my listening taste still has a degree of “cool” and Kylie is said to be less mainstream than Queen and the Rolling Stones. I have truly become my parents.

Faithless make a podium appearance after I finally got around to ripping a bunch of their CDs while Jacob Israel scored scrobbles because I submitted three of his albums to Discogs. The same goes for Messrs. Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Strauß, Pyotr Tchaikovsky and a host of others (including Alfons Bauer) — but those were vinyl records. They obviously weren’t scrobbled, leading to twisted and distorted data that reflects nothing unless you know its source and understand its context.

As for Limahl’s Never Ending Story? There goes my street cred.

Fact is that it’s just one of eight tunes that, due to random selection, happened to get played five times last year according to Last.fm. It means nothing.

Somewhat more meaningful are the “artist origins” (if known to MusicBrainz).

This doesn’t necessarily mean I’m biased.

All it confirms is that I prefer to listen to songs whose lyrics are in languages I can understand. This information is largely useless but the moment you flip the data around it can be worth gold: Where are an artist’s most devout listeners located? Spotify and the like know their listeners suspiciously well, and artists can harvest this data for their own and their fans’ benefit (such as for planning tours). Now this is useful.

Most interesting, though, is the graph below:

As a child of the eighties I’d have firmly expected this to be the decade of my most-listened-to tunes. Randomness should have levelled the playing field to a certain extent, with some personal interference (read: manual selection) favouring music from that era — but that’s apparently not the case.

“When do the strongest adult musical preferences set in? For women, it’s age 13; for men, it’s a bit later, 14.” —

I was at a complete loss — until I realised that this chart is based on “listens”, not “loves”, and these listens are ultimately based on “haves” in MP3 form. The good stuff… the songs I really love, the songs that have emotional meaning to me — those I’ve got on CD or vinyl (nowadays considered less a music carrier than a piece of merchandise).

“In fact, it’s the newest artists that are now selling [vinyl]. Artists who’s first release came in 2020 found that vinyl made up almost 60% of their merch sales, while artists who’s first release came before 1980 found that it composed only around 24% of their sales.” — Bobby Owsinski

The latest IFPI Report confirms that “the demand for physical music continues” and that “58% of vinyl buyers were typically between the ages of 25-44 years old”.

On the one hand this surprises me, on the other it doesn’t when you factor in financial responsibilities vs. convenience as a person’s priorities change with age. How Spotify would know about (all) vinyl sales remains undisclosed, and it’s equally worrisome how some of this data may be used to influence peoples’ listening habits. It wouldn’t surprise me if there’s an unfinished Black Mirror script out there about AI-generated music supported by a bot-driven social media presence and StyleGAN-created looks that storms up the future charts.

“Our data has shown that we can typically predict 33 days in advance what’s going to be at the top of the Billboard Hot 100. It’s fun to see the epidemic start to spread — the growth of these songs, starting in a city.” — Shazam

It seems that Spotify isn’t in the music business after all; instead, they provide data based on its consumption (which is often more exciting than the music itself).

Let’s see how I can manipulate my listening data for next year’s charts.

All screenshots by hmvhDOTnet unless indicated otherwise